The futile class struggle of Parasite

Bong Joon-Ho’s Palme d’Or winning film Parasite is a genre-bending affixation of class anxiety. It hopes to examine economic inequality but its calculative and measured approach to class conflict falls short of a radical assessment of capitalism. “We all live in the same country now: that of capitalism,” as the director puts it to The Hollywood Reporter. Yet, the film’s treatment of the working class of South Korea resorts to a neoliberal fallacy that capitalism is the only way the world can continue to exist. What Parasite does well is bring audiences into theatres for a foreign language comedy-drama-thriller with a socially relevant narrative arc. Where it fails, is in expanding that ideological scope into off-screen class consciousness.

The film opens with Kim Ki-Woo (Choi Woo-Shik), fishing for a neighbour’s unlocked wifi access in a half-basement that is the Kim family residence, located in an impoverished neighbourhood of Seoul. The family of four, including Ki-woo, consists of Ki-Jeong (Park So-dam) the sister, Ki-taek (Song Ka-ho) the father, and Chung-sook (Jang Hye-Ji) the mother. Bong introduces the family as a portrait of the grotesque underclass of South Korea, barely granted the right to dignity. Despite the family’s obvious wit and merit, their only tool of survival seems to be their tongue-in-cheek humour as they fold one pizza box after another for a piece-wage.

Early in the film, a drunk homeless man prepares to urinate at the Kim family’s window, the only part of the house that is above ground and looks over to the outside world. As Ki-woo protests this act, the man threatens to urinate at him in return. This is when Ki-woo’s wealthy school friend, Min, pops by in front of their house and demands the drunkard to stop – which he does, due to Min’s commanding aura that can only be granted to someone who was born privileged. Min brings with him a present for the family – a scholar’s stone from Min’s grandfather’s collection, that is believed to bring wealth to the family who possesses it. Ki-woo, in absurdist humour, exclaims, “Metaphorical!”

Metaphorical indeed because Min also offers Ki-woo a job as an English tutor to the daughter of a rich businessman. Ki-woo is hesitant at first, protesting that he has no qualifications for the job. But Min reassures, as only someone who was born privileged can do, that it is all about self-belief and confidence. And so, Ki-woo takes up the offer and goes for the job interview at the wealthy Park family’s residence, backed by a forged diploma courtesy of his sister Ki-Jeong.

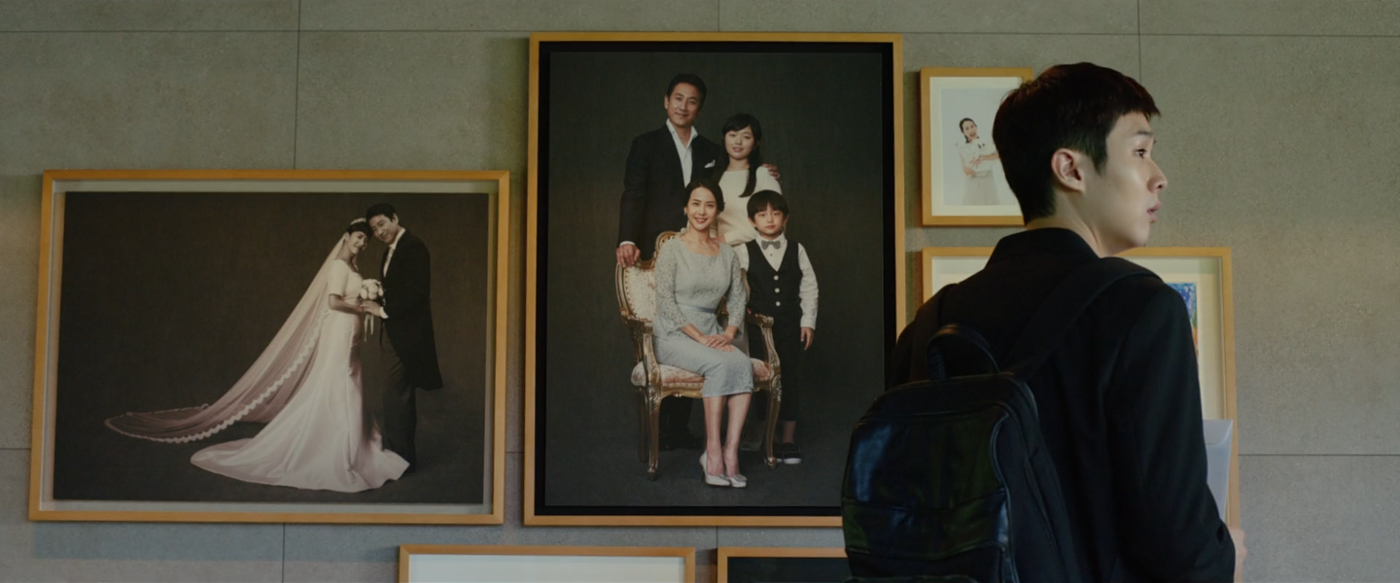

The first look at the Park’s home signals modernity with its present and expansive architecture. The manicured lawn and sterile glass walls appear offensively pleasant compared to the Kim’s half-basement. Park Yeon-gyo (Cho Yeo-jeong) is the “simple” wife of the wealthy businessman Park Dong-ik (Lee Sun-kyun). Together, they have a teenage daughter Da-hye (Jung Ji-so) and a disturbed but artistic son, Da-song. The house is maintained by the family’s loyal housekeeper and chauffeur.

It only makes sense in the unfair scheme of things, that the inhabitants of such an elegant space would be the gullible young mother Yeon-gyo who takes to Ki-woo’s faux-polished demeanour and his American degree with admiration. In subtle steps, Ki-woo leeches off the persona of his elite friend, Min – so much so that he begins a romance with Min’s former student and love interest, Da-hye.

But this is truly just the beginning of a creeping invasion of the four Kims on the four Parks. One by one, Ki-woo conspires to replace the household staff with his family members – playing on a key mechanism favoured unapologetically by the rich: nepotism.

The Park family’s naivety and niceness is a consequence of their removed and sheltered experience, as claimed by Chung-sook one night when the owners are out camping. The Kim family is living large in the grand house while their rich employers are away. That is, until the terminated former housekeeper shows up at the door asking to be let in.

What entails next is a true moment of revelation that not only captivates the emotional capacity of the audience but also gravitates them towards the truth of the subaltern – a class beneath that of the working class. The former housekeeper confesses that her husband has been hiding in the bunker (a level lower than the basement) to evade loan sharks. The tension between the two underclass families, however, result in a clash of great comedic catastrophe. The joy of watching Parasite rests in this middle act where the diegesis oscillates between and beyond the definitive knowledge of genre films. Class warfare peaks in these horror elements engulfing the screen in excess violence and punch-drunk entertainment.

Parasite truly exhibits Bong’s genius – he leverages the box-office quality of his films into a critical realm of political art. He “weaponizes” the American blockbuster cinema, as Slate calls it. But it is the very nature of American cinema that betrays class consciousness in Parasite.

Hollywood has time overtime failed to approach the issue of class critically through its canon of films and the benchmark set for Parasite, quite honestly, is rather low. A quick look at the Best Picture nominations at the Oscars from the last decade shows an obvious lack of class narratives save for few period dramas. That makes sense because period dramas allow the North American (and by extension of Hollywood’s cultural hegemony, a global audience) to look at inequality from a point of passing.

None of the films from the Academy’s Best Picture Nomination from 2010 to present actively address the pressing issues of contemporary social justice. For Parasite to function in this context and to provide what can only be considered a simplified understanding of class at best, is an easy game for an audience starving for stories that seemingly critique an unjust and corrupt system. While the matter of class may have seeped into the backgrounds of several films due to its intersectional nature, it is rare to find a film of Parasite’s scale that is solely and absolutely about this conflict.

The blockbuster style is wired to provide entertainment and falls short when it comes to carrying out a meaningful interrogation into political and economic realities– such as in the birthday party scene in Parasite.

The Park family decides to heal their son’s childhood trauma of seeing a ghost on his birthday by finally hosting his birthday party at their home this year. The party occurs after a disastrous thunderstorm which destroys not only the Kim family’s half-basement but also their entire neighbourhood. Having witnessed the catastrophe onscreen, it is difficult to digest that there exists a class of people who will never be affected by such events. No matter how many families become homeless overnight, for the rich and the glamorous, a birthday party takes precedence. Members of the ruling class in Parasite faithfully deliver on their vanity. Da-song’s beautiful birthday is attended by pristine and perfect looking guests, unaffected and unaware of the catastrophe from the previous night.

The birthday soon turns violent as the husband from the bunker strikes back and attacks the guests, killing Ki-jeong. The characters’ actions swing between slapstick and slasher, leaving the audience at indecision to whether to laugh or to gasp (I’ve seen both happen in the theatre, and some in-between reactions too). The variety of emotions generated by the birthday party scene only testifies to the power of spectacle that it holds.

The spectacle, however, acts dually in engagement and disengagement with the core narrative. The diegesis has been largely on the side of the oppressed so far. But the moment Mr. Kim stabs his employer, Bong Joon-Ho is no longer on the side of the oppressed. With its last act, Bong essentially creates a class revolution onscreen. But when he does so, it pauses the offscreen revolution that would arise from the audience if they were left to confront the indifference of the elites.

As we sympathise with the Kims, we grow more and more antagonistic towards the Parks for being thoughtless and insensitive and ostentatious. We are frustrated with the realization that no amount of hard work and intelligence can topple the structural barriers to success. Our anger longs for an actionable outcome which is resolved with the stabbing of Dong-ik; and thereby subjugating our burning need for an actionable outcome in the real world.

With Parasite, we find comedic relief from capitalism in a timeless fashion that can only be called artfully Hollywood. The change of times has called for greater diversity and representation on screen and finally, we are seeing something of Bong’s stature. Yet, it is no wonder that mainstream acclaim is still reserved for easily digestible stories. In Parasite, Bong holds up to us, a mirror of society. However, one wonders what this mirror can do for us? What can merely a representation of the working class provide to the conversation of dismantling capitalism?

Parasite is a class story for the compradors – for bourgeois audiences like me who can find humour in the darkness of capitalist exploitation. As Ki-woo aspires to be rich enough to buy the Park house and unite with his father, the parting message is that this is the way the world is and there’s nothing that we can do about it. Ki-woo falls back to a cycle that only creates more roaches and leeches and parasites. As bourgeois audiences, this mirroring sits comfortably with us because we are only capable of grasping the tragedy of capitalism but not able to reimagine an escape out of it. And as we leave the theatre, our class struggle ends there. We return to our warm and comfortable homes and read up on why this film is so great. It eases up to our conscious because we can agree with the film without having to feel suffocated by capitalism. Bong Joon-Ho, while well-intentioned, ultimately provides a respite from capitalism, instead of a resistance to it.